¶ Environment and Social Impact Assessments

Until recently, forests were treated as an infinite supply of physical and biological resources to be used for human benefit and exploited whenever wanted. Forestry operations were assessed purely in silvicultural and financial terms without economic valuation of non-cash benefits and without environmental considerations. It is the policy of the GoU that ESIA be conducted for proposed activities that may, are likely to, or will have significant impacts on the environment. ESIA is a tool for protecting the environment.

The use of ESIA ensures that environmental impacts are considered during conception, design and implementation of development activities at the same time that financial, technical and institutional aspects of the project are considered. ESIA is a systematic and interdisciplinary evaluation of the potential positive and negative environmental effects of a proposed action and its practical alternatives on the physical, biological, cultural and socio-economic attributes of a particular geographical area.

The developer is responsible for the ESIA in accordance with the general guidelines on the conduct of the assessment, the provisions of the National Environmental Act No. 9 of 2019, and the National Environment (Environmental and Social Assessment) Regulations, No.143 of 2020.

¶ The Mitigation Hierarchy

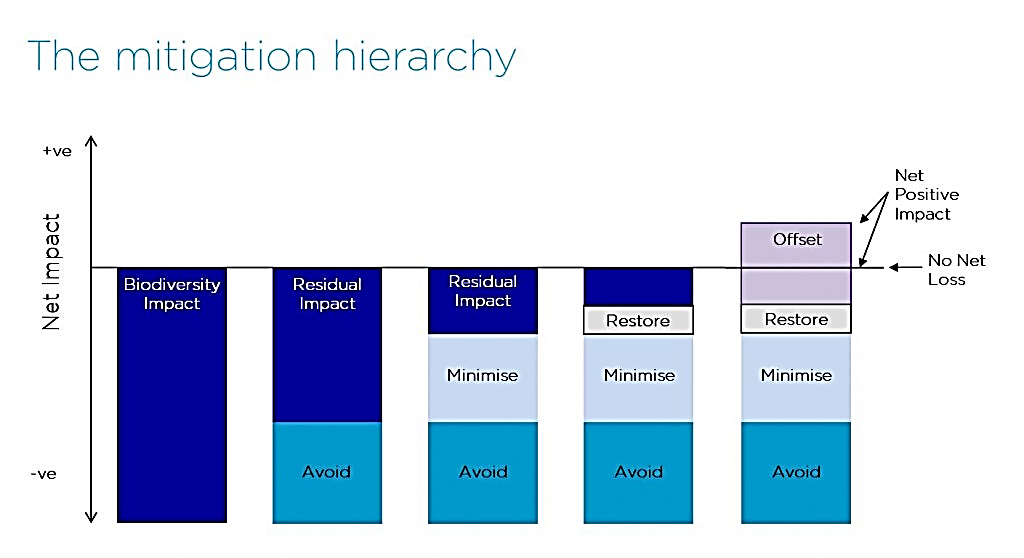

The mitigation hierarchy is crucial for all development projects aiming to achieve no overall negative impact on biodiversity, or on balance, a net gain (also referred to a No Net Loss and the Net Positive Approach). It is based on a series of essential, sequential steps that must be taken throughout the project’s life cycle in order to limit any negative impacts on environment and biodiversity. The sequential steps of the mitigation hierarch include avoidance, minimisation, rehabilitation/restoration and offset (Figure 19).

Figure 19: The Mitigation Hierarchy

Source: https://www.thebiodiversityconsultancy.com/approaches/mitigation-hierarchy/

Avoidance is the first step of the mitigation hierarchy and comprises measures taken to avoid creating impacts from the outset, such as careful spatial or temporal placement of infrastructure or disturbance. For example, placement of roads outside of rare habitats or kesny species’ breeding grounds, or timing of seismic operations when herds of elephants are not present. Avoidance is often the easiest, cheapest and most effective way of reducing potential negative impacts, but it requires that biodiversity be considered in the early stages of a project.

Minimisation includes measures taken to reduce the duration, intensity and/or extent of impacts that cannot be completely avoided. Effective minimisation can eliminate some negative impacts. Examples include such measures as reducing noise and pollution, designing power lines to reduce the likelihood of bird electrocutions, or building wildlife crossings on roads.

Rehabilitation/restoration are measures taken to improve degraded or removed ecosystems following exposure to impacts that cannot be completely avoided or minimised. Restoration tries to return an area to the original ecosystem that occurred before impacts, whereas rehabilitation only aims to restore basic ecological functions and/or ecosystem services (e.g. through planting trees to stabilise bare soil). Rehabilitation and restoration are frequently needed towards the end of a project’s life-cycle, but may be possible in some areas during operation (e.g. after temporary borrow pits have fulfilled their use).

Collectively avoidance, minimisation and rehabilitation/restoration serve to reduce, as far as possible, the residual impacts that a project has on environment/biodiversity. Typically, however, even after their effective application, additional steps will be required to achieve no overall negative impact or a net gain for biodiversity.

Biodiversity offsets are measurable conservation outcomes resulting from actions designed to compensate for significant residual adverse biodiversity and related social impacts arising from project development after appropriate prevention or avoidance measures, minimization measures, and rehabilitation or restoration on site have been considered. Biodiversity offsets are of three main types: ‘restoration offsets’ which aim to rehabilitate or restore degraded habitat; ‘averted loss offsets’ which aim to reduce or stop biodiversity loss (e.g., future habitat degradation) in areas where this is predicted; and compensation packages - used where stakeholders whose use and cultural values of biodiversity, including livelihood assets, and/ or their access to natural resources (e.g. water, grazing or cropping land, forests) have been negatively affected by either the development or the offset, and cannot be remedied at the proposed offset site[1] . Offsets are often complex and expensive, and should always be the last resort, and so attention to earlier steps in the mitigation hierarchy is usually preferable.

The design of offsets should exclude irreplaceable areas and areas where development is likely to result in ‘non-offsetable’ impacts. ‘Non-offsetable impacts’ refers to a level of severity of residual negative impacts at and beyond which a development project would not be able to offset. For example, it is not possible to offset the extinction of a species, the irreplaceable loss of a unique ecosystem, or permanently alter natural cycles.

¶ Strategic Environmental Assessment

Section 47 of the National Environment Act, 2019, and Regulation 10 of the Strategic Environment Assessment Regulations, No. 50 of 2020, require that a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) be undertaken for government policies, plans and programmes being initiated or reviewed, which are likely to have a significant impact on human health or the environment[2] . Broadly, a SEA process is defined as a study of the impacts of a proposed project, plan, policy or legislative action on the environment and sustainability. It is a systematic and anticipatory process, undertaken to analyse the environmental effects of proposed strategic actions and to integrate the findings into decision-making. Its purpose is to:

The purpose of a strategic environmental assessment is to:

• Identify and describe the environmental, health and social objectives to be achieved by the policy, plan or programme;

• Identify potential impacts of a policy, plan or programme on human health and the environment;

• Identify public interests;

• Determine the cost effectiveness of the policy, plan or programme; and

• Determine any other strategic goals.

The aim of SEA is to ensure that environmental considerations inform, and are integrated into strategic decision-making in support of environmentally sound and sustainable development. In particular, the SEA process assists authorities responsible for plans and programmes, as well as decision-makers, to take into account:

• Key environmental trends, potentials and constraints that may affect or may be affected by the plan or programme;

• Environmental objectives and indicators that are relevant to the plan or programme;

• Likely significant environmental effects of proposed options and the implementation of the plan or programme;

• Measures to avoid, reduce or mitigate adverse effects and to enhance positive effects; and

• Views and information from relevant authorities, the public and - as and when relevant - potentially affected landscapes;

SEA has evolved largely as an extension of ESIA principles, process and procedure but it also offers a number of advantages compared to the ESIA of projects. The advantages follow from the SEA application to the higher level of plan and programme making, which sets a framework for projects subject to ESIA and potentially many other actions that may have an impact on the environment. At this level, SEA facilitates consideration of the environment in relation to fundamental issues (why, where and what form of development) rather than addressing only how an individual project should be developed. The potential for environmental gain is much higher with SEA than with ESIA. In that regard, the specific value added by SEA to plans and programmes includes:

(i) The opportunity to consider a wider range of alternatives and options at this level compared with the project stage;

(ii) Influencing the type and location of development that takes place in a sector or region, rather than just the design or siting of an individual project;

(iii) Enhanced capability to address cumulative and large-scale effects within the time and space boundaries of plans and programmes as opposed to the project level;

(iv) Facilitating the delivery of sustainable development through addressing the consistency of plan and programme objectives and options with relevant strategies, policies and commitments; and

(v) Streamlining and strengthening project ESIA by ‘tiering’ this process to the SEA report and thereby avoiding questions (whether, where and what type of development should take place) that have been decided already with environmental input.

The immediate benefits of SEA application can be found in information that assists sound decision-making and in the consequent gains achieved in environmental protection and sustainable development. In addition, there are other, secondary benefits that are integral to the participatory approach and transparent procedures followed in accordance the SEA process. When properly implemented, the SEA process should:

(i) Provide for a high level of environmental protection;

(ii) Improve the quality of plan and programme making;

(iii) Increase the efficiency of decision-making;

(iv) Facilitate the identification of new opportunities for development;

(v) Help to prevent costly mistakes;

(vi) Strengthen governance; and

(vii) Facilitate trans-boundary cooperation.

Instruction 482: There are a number of general guiding principles for the application of a SEA. These generally include various statements in national guidance materials or in the literature of the environment field. More specifically, SEA should:

(i) Be undertaken by the authority responsible for a plan or programme. Ideally it should be integrated into and customized to the logic of the plan- or programme-making process.

(ii) Be applied as early as possible in the decision-making process when all the alternatives and options remain open for consideration.

(iii) Focus on the key issues that matter in the relevant stages of the plan- or programme-making process. This will facilitate the process being undertaken in a timely, cost-effective and credible manner.

(iv) Evaluate a reasonable range of alternatives, recognizing that their scope will vary with the level of decision-making. Wherever possible and appropriate, it should identify the best practicable environmental option.

(v) Provide appropriate opportunities for the involvement of key stakeholders and the public, beginning at an early stage in the process and carried out through clear procedures. It should employ easy-to-use consultation techniques that are suitable for the target groups.

(vi) Be carried out with appropriate and cost-effective methods and techniques of analysis. It should achieve its objectives within the limits of the available information, time and resources and should gather information only in the amount and detail necessary for sound decision-making.

Instruction 483: For the following areas, impacts are not offsetable, and therefore should be considered to be “no-go areas” for development:

i) Environmentally sensitive areas[3] and fragile ecosystems[4] (as defined in the National Environment Act, 2019);

ii) Areas with high biodiversity conservation values, with localised endemic and threatened species; Critical Habitats;

iii) UNESCO Man and the Biosphere (MAB) areas for which any negative impacts are considered not to be offsetable given their value for biodiversity conservation and/ or people including World Heritage Sites, Ramsar Sites, key biodiversity areas (KBAs)[5] , protected areas and existing offset areas[6] .

iv) Areas with irreplaceable biodiversity or natural resources providing ecosystem services which are of high social value, on which there is a high level of dependence for health, safety, livelihoods or wellbeing, and for which there is no affordable, acceptable or accessible substitute. e.g. loss of irreplaceable biodiversity and/ or use or cultural values of biodiversity considered to be a priority by affected people which could not be offset, replaced or compensated, would be described as ‘non offsetable’.

v) Areas with high cultural value as natural heritage sites, or highly valued by local communities or indigenous people, generally have no substitute (i.e., are regarded as non-offsetable cultural assets for current and future generations).

vi) Cases where there are very high risks of failure to implement the offset successfully (i.e., there are ecological, technical, socio-cultural, institutional, financial and/or legal or land tenure factors that influence the practical feasibility of achieving No Net Loss), including lack of adequate assurances or guarantees that the requirements for a successful offset outcome can and will be met.

¶ Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA)

Part X of the NEA provides for a process to be followed in conducting ESIAs. Although the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) is responsible for the development of guidelines for implementing ESIA, the Lead Agencies are under legal obligation to develop and implement sector-specific ESIA guidelines. However, the guidelines have to be cleared with the NEMA to ensure their conformity and compatibility with the law. Schedule 3 of the NEA lists projects that have to be considered for ESIA, including forestry related activities. Forest management related activities that require ESIA include:

(i) Establishment of wildlife areas;

(ii) Formulation or modification of forest management policies;

(iii) Formulation or modification of water catchment management policies;

(iv) Policies for management of ecosystems, especially by use of fire;

(v) Commercial exploitation of natural fauna and flora; and

(vi) Introduction of alien species of fauna and flora into ecosystems.

NFA prepared Guidelines for Environmental Impact Assessment of Forestry Developments in 2005. They were submitted to NEMA but they have not yet been approved.

Instruction 484: The Ministry responsible for forestry (DEA, FSSD, and NFA) should work with NEMA to develop the ESIA guidelines for forest operations in the forestry Sector. The FMIs shall ensure that their organisation’s units at all levels keep copies of, and be familiar with, the guidelines and requirements.

Instruction 485: in addition to the activities for forestry listed in Schedule 5 of the National Environment Act, the following shall be considered for ESIA:

(i) Staff house construction.

(ii) Primate viewing and high usage nature trails.

(iii) Construction of camping facilities.

(iv) Improvement of existing accommodation facilities.

(v) Road construction and maintenance.

(vi) Construction of upstream and midstream petroleum infrastructure.

(vii) Construction of visitor centres, hotels and lodges.

(viii) Activities in forests which are in their natural state before exploitation

Instruction 486: The ESIA process shall include the following steps:

(ii) Screening which determines whether a proposed project or activity should be subject to the ESIA and, if so, at what level of detail.

(iii) Scoping which identifies the issues and effects that are likely to be of significance and it establishes Terms of Reference (TOR) for the ESIA.

(iv) Examination of alternatives which establishes the preferred or most environmentally sound option for achieving proposal objectives.

(v) Impact analysis which identifies and predicts the likely environmental, social and other related impacts of the proposed project or activity.

(vi) Mitigation and impact management which establishes the measures and steps to be taken that are necessary to avoid, minimise or offset predicted adverse effects (mitigation hierarchy) and it incorporates these into an environmental management and monitoring plan or system (subject to the Precautionary Approach defined in Box 3 above)

(vii) Evaluation of significance which determines the importance and acceptability of residual effects, and the need for biodiversity and social offsets.

(viii) Preparation of ESIA that clearly and impartially Handbooks the effects of the proposed project or activity, proposed mitigation measures, and the significance of effects and concerns of relevant stakeholders, including interested communities affected by the project or activity.

(ix) Review of the EIA which determines whether the report meets its TOR, provides a satisfactory assessment of the proposed project or activity and contains the information required for decision-making.

(x) Decision-making which either approves or rejects the proposed project and establishes the terms and conditions for its implementation.

(xi) Follow up which ensures that the terms and conditions of approval are met, and it monitors the effects of development and the effectiveness of mitigation measures. In addition, it strengthens future ESIA applications and mitigation measures. Where required, environmental audits shall be conducted to evaluate and ensure the optimisation of environmental management.

Instruction 487: Section 7(1) (c) of Forestry Act, 2003 obliges the Minister to carry out an Environment Impact Assessment before declaring a CFR. The assessment shall be preceded by a SEA as CFRs often traverse varieties of landscapes and are supposed to be done before and/or during decision making. Strategic and business plans of FMIs and DDPs should be subjected to SEA.

¶ Preparation and Use of Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps[7]

Sensitivity maps present spatial data on the sensitivity of assets to any given pressure, such as the sensitivity of natural forests to oil spills. Assets that are considered vulnerable are those that are sensitive and exposed to a given pressure (UNEP-WCMC, 2019). Sensitivity is usually a measure of whether an asset is:

• Environmentally, culturally or economically significant;

• At risk of being exposed to any given pressure; and/or

• At risk of being negatively affected by the pressure.

The overall objective of the Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps is to contribute towards maintaining the integrity of a PA, or an environmentally sensitive landscape and/or ecosystem. The Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps mapping process:

(i) Identifies and maps ecologically sensitive areas;

(ii) Provides the environmental authorities with an overview of the major environmental concerns vis-à-vis industrial and other developments in a PA, landscapes and or ecosystem;

(iii) Provides a scientific tool to guide decision making;

(iv) Provides the environmental authorities with a tool for planning and a baseline for the necessary research and monitoring;

(v) Indicates the potential environmental impacts of greatest significance, based on scenarios and plans, for industrial development and the best available understanding of ecological processes;

(vi) Enhances ability to respond to and assimilate alterations in scenarios for industrial development and new knowledge concerning ecological conditions in the specific area;

(vii) Represents the views of a broad range of specialists with the experience required from industrial activities, research and environmental management;

(viii) Is one of the tools that will enable developers and investors operating in a PA, landscape and/or ecosystem to avoid, where possible, and/or minimize destruction of ecologically sensitive areas;

(ix) Helps PA managers and other relevant authorities in knowing where to focus their efforts in case there is a negative impact from the developments and to provide timely and appropriate response and clean-up strategies; and

(x) Identifies information gaps on sensitive areas such as breeding grounds, areas with high aggregations of wildlife, watering points, critical habitats for wildlife and gradients susceptible to erosion and landslides. These areas need to be identified so that care is taken to avoid and/ or minimise impacts.

The concept of Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps is the spirit behind Section 6(2) (a) – (b) of the Forestry Act. FMP maps shall clearly indicate environmentally and ecologically sensitive areas and demarcated on the ground using methods as shall have been determined by the RB. ESIA, SEA and Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps processes inform decision making and herein lies their value.

Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps are usually prepared using GIS, which requires software and hardware, GIS skills, and spatial data which is not likely to be found at most FMUs. Therefore, this work will often be led from the FMI Headquarters but with active participation of field staff. GIS notwithstanding, it is also important to engage stakeholders to augment the understanding of sensitivity, especially with respect to social sensitivities. Below is an outline of the main stages in preparing and Environmental Sensitivity Atlases/ Maps.

(i) Identification and mapping of sensitive biodiversity or socio economic assets

A sensitivity map should align with the scope of the potentially affected area. For example, the map should cover the areas along the entire high tension electricity transmission line, not just the PA only. Sensitivity maps should consider:

a) Asset type and its general environmental sensitivity to the given pressure. For example forest cover in an ecotourism section of the CFR and the sensitivity of the forest cover to high numbers of tourists

b) Sensitive ecosystems, habitats, species and other key natural assets

c) Sensitive socio-economic assets like cultural sites, tourist attractions, etc.

The identification and mapping process of the sensitive assets should be simple and exploratory, with the aim of understanding the range and location of assets that may be affected by the given pressure. The result of this stage is a map of potentially sensitive assets.

(ii) Prioritisation and ranking of assets

This stage helps in establishing the relative sensitivity and/or importance of different assets by area. This stage attaches relative values (not necessarily financial) to each asset. This is where stakeholder engagement comes in to complement computer aided sensitivity methods. However, it is also important to note that some sensitive assets of ecological importance may not be recognised as valuable by stakeholders, but they should also be included. On the other hand, available data may not include all valuable assets, and the sensitivity should be established through the precautionary principle (Box 3 above).

The data obtained through prioritisation and ranking of assets is aggregated by an expert using computer models in order to produce a map that uses colour codes to represent different types of assets and their sensitivities.

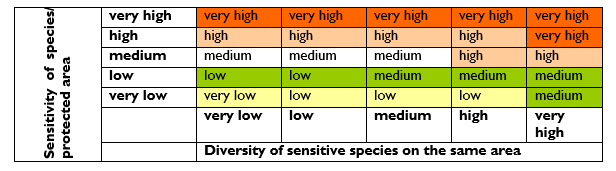

Another way of aggregating species data would be to sum the number of sensitive species in a grid (i.e. sensitive species richness). A simple matrix can be used to establish a sensitivity ranking for an area where a diverse range of sensitive species is present, by comparing the sensitivity of the species/ PA with the diversity of species in that area (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Matrix for Establishing the Sensitivity of an Area

Figure 20: Matrix for Establishing the Sensitivity of an Area

Source: NEA and UNEP-WCMC (2019). Environmental sensitivity mapping for oil & gas development: A high-level review of methodologies

(iii) Producing an integrated sensitivity map

The sensitivity maps are used in designing site-specific protection and detailed operations in response to given pressures on the asset. The sensitivity maps integrate ecological and socio-economic information. The mapping method depends on the user requirements, and thus the intended mapping outputs and uses, including the targeted assets, management phase, types of pressures, and the level of detail required by the user. For example, the atlas may be used in Strategic Environmental Assessment, preparation of a DFDP, a FMP, as part of an ESIA process applied at the project level.

An example of the table of contents of an environmental sensitivity atlas is presented below.

-

Background

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Conservation Values of Queen Elizabeth Protected Area (QEPA) Ecosystems

1.2 Developments in QEPA

1.3 Justification

1.4 Objectives of the QEPA Sensitivity Atlas

1.5 Process of Developing the Sensitivity Atlas

1.6 Review of the Sensitivity Atlas -

Biological, Physical and Socio-Economic Environments

2.0 Introduction

2.1 Biological Environment

2.2 Physical Environment

2.3 Socio-economic Environment -

Status and Distribution of Biological and Physical Environments

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Status and Distribution of Biological Environment

3.3 Distribution of Animal Species

3.4 Distribution of Critical Areas for Animal Survival -

Sensitivity Analysis of QEPA

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Sensitivity Ranking

4.3 Sensitivity of components

4.4 Vulnerability Index Modeling of QEPA

4.5 Mammal Species Sensitivity

4.6 Sensitivity of the Biological Components

4.7 Sensitivity of the Critical Areas of Animal Survival

4.8 Overall Biological Sensitivity Map of QEPA -

Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1 Conclusion

5.2 Recommendations

Bibliography

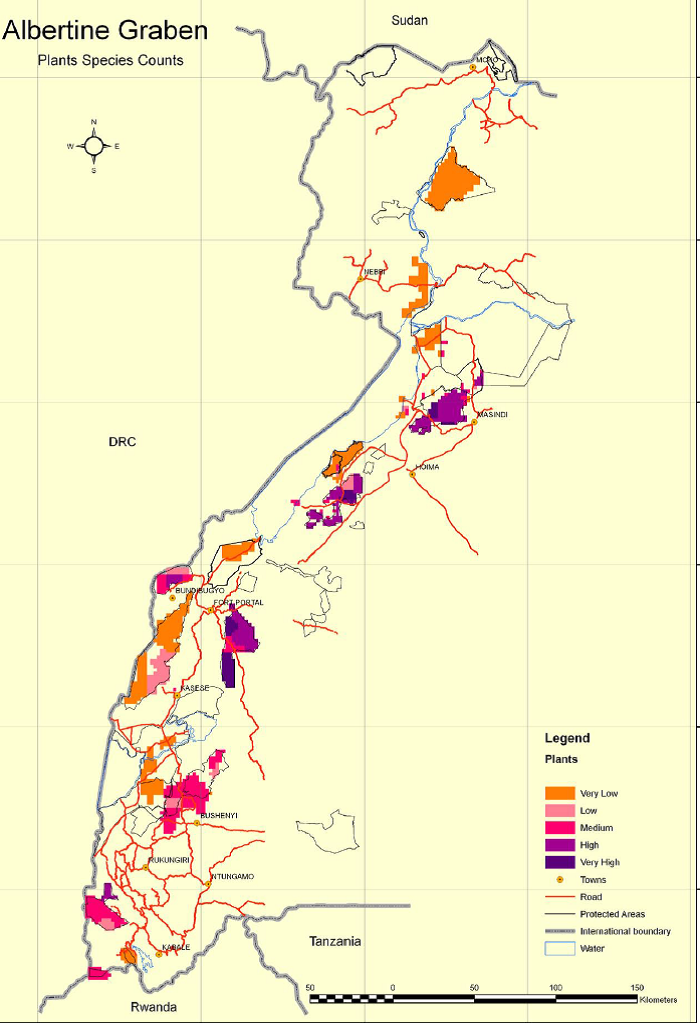

A sample map from an Environment Sensitivity Atlas/ Map is shown in Figure 21. It is from the Environmental Sensitivity Atlas for Queen Elizabeth Protected Area.

Figure 21: A Sample Map for Plant Species Counts for the Albertine Graben

Extracted from NEMA, 2010. Environmental Sensitivity Atlas for the Albertine Graben 2010

Instruction 488: The methods summarised in Annex 2 of UNEP-WCMC (2019) – Fact Sheets, may be customized and developed in detail by FMIs for use in preparing own sensitivity atlases

Instruction 489: Because the resources (funds and expertise) needed to prepare a good environmental sensitivity atlas are considerable, the FMIs may share their atlases, or they may combine resources to produce and keep updated the atlases. Updating the atlases should be done at least once every 5-10 years, unless it becomes necessary to do it earlier for one reason or another

Instruction 490: At the very least, District Environment Action Plans, DFDPs, and FMPs shall include a map indicating sensitive landscapes and ecosystems.

National Environment Management Authority, 2020. National guidelines for biodiversity and social offsets in Uganda ↩︎

Government of Uganda, 2019. The National Environment Act, 2019 ↩︎

Schedule 10 of the National Environment Act, 2019 ↩︎

Fragile ecosystems include deserts, semi–arid lands, mountains, wetlands, small islands and coastal areas ↩︎

A total of 36 KBA sites, which include terrestrial, wetland and freshwater sites have been identified for Uganda. Ten of these sites lie outside protected areas, e.g., Tororo Rock, Lake Bisina, Lake Nakuwa and Lake Napeta (BSOS 2019). ↩︎

The IUCN Red List, the National Red List for Uganda, Uganda’s protected area list and KBAs, are important sources of information ↩︎

NEA and UNEP-WCMC (2019). Environmental sensitivity mapping for oil & gas development: A high-level review of methodologies ↩︎