¶ Management of Forest Landscapes

¶ What is a Forest Landscape?

A forest landscape is a geographical area of any size, where a forest is a key vegetation component. It may refer to an area with interconnected forests or ecosystems, and therefore, “landscape” and “ecosystem” are often used interchangeably. Landscapes are delineated on the ground depending on the management objectives, land use systems. The landscape may be one forest and its environs, or several forests in a given geographical area, connected through a variety of land uses. In practice, forest landscapes in Uganda can be interpreted to refer to:

• Areas delineated for purposes of conservation of biological diversity e.g. the Albertine Rift Forests

• The four Water Management Zones of the MWE, with a Regional Forest Office in each Zone

• The Uganda Bio-geographical Provinces delineated in the Uganda Country Study on Costs, Benefits and Unmet Needs of Biological Diversity Conservation (UNEP, 1992)

• The seven landscapes delineated in the Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunity Assessment for Uganda (MWE & IUCN, 2016)

• Uganda’s nine Agro-ecological Zones

• NFA’s nine Administrative Ranges or each sector under each of those Ranges (NFA Strategic Plan, 2020-2025)

• Forest Management Plan Areas that cover a number forests

• Etc.

¶ Principles of the Landscape Approach

A landscape approach to managing forests provides opportunities for managing land to achieve social, economic, and environmental objectives amidst land uses that interact with forestry. Such land uses commonly include agriculture, livestock, wildlife, mining, watersheds, fisheries, wetlands, among others.

The 10 principles of the landscape approach to natural resource management outlined below have been widely discussed through intergovernmental and inter-institutional processes, and accepted by the Convention on Biological Diversity, to which Uganda is a signatory.

The principles point to how agricultural production and environmental conservation can best be integrated at a landscape scale [1].

(i) Principle 1: Continual learning and adaptive management

Because there are a number of components in a landscape, implementers continuously learn during implementation and this learning goes beyond forestry to the disciplines that interact with forestry. As new knowledge becomes available from a variety of interventions, actions are revised accordingly.

(ii) Principle 2: Common concern entry point

Solutions to problems need to be built on shared negotiation processes based on trust among the actors. Trust emerges when objectives and values are shared. However, full consensus is often difficult to achieve because stakeholders have different values, beliefs, and objectives. Therefore identifying immediate ways forward through addressing simpler short-term objectives can begin to build trust. Each stakeholder will only join the process if they judge it to be in their interest. Launching the process by focusing on easy-to-reach intermediate targets may provide a basis for stakeholders to begin to work together.

(iii) Principle 3: Multiple scales

Multiple processes at various levels affect the overall landscape approach. Awareness of these processes can improve local interventions, inform higher-level policy and governance, and help coordinate administrative entities.

(iv) Principle 4: Multi-functionality

Many landscapes provide a diverse range of values, goods, and services. The landscape approach acknowledges the various tradeoffs among these goods and services.

(v) Principle 5: Multiple stakeholders

Multiple stakeholders frame and express objectives in different ways. Stakeholders should therefore be engaged equitably in decision-making processes. All stakeholders should be recognized, even though efficient pursuit of negotiated solutions may involve a subset of the stakeholders. Solutions should encompass a fair distribution of benefits and incentives. Progress requires communication, which needs to be developed and nurtured, and mutual respect of values is essential. There is often a need to address conflicts, and issues of trust and power.

(vi) Principle 6: Negotiated and transparent change logic

Trust among stakeholders is a basis for good management and is needed to avoid or resolve conflicts. Transparency is the basis of trust, and is achieved through a mutually understood and negotiated process of change, helped by good governance. The need to coordinate activities by diverse actors requires that a shared vision can be agreed upon, and achieving broad consensus on general goals, challenges, and concerns, as well as on options and opportunities. All stakeholders need to understand and accept the general logic, legitimacy, and justification for a course of action, and to be aware of the risks and uncertainties. Building and maintaining such a consensus is a fundamental goal of a landscape approach

(vii) Principle 7: Clarification of rights and responsibilities

Rules on access to resources and land use need to be clear as a basis for good management. Access to a fair justice system allows for conflict resolution and recourse. The rights and responsibilities of different actors need to be clear to, and accepted by, all stakeholders. When conflict arises, there needs to be an accepted legitimate system for arbitration, justice, and reconciliation.

(viii) Principle 8: Participatory and user-friendly monitoring

In a landscape approach, no single stakeholder can claim to have all the relevant information. All stakeholders should be able to generate, gather, and integrate the information they require to interpret activities, progress, and threats. To facilitate shared learning, information needs to be widely accessible, systems that integrate different kinds of information need to be developed and used. When stakeholders have agreed on desirable actions and outcomes, they should also be involved in assessing progress, and updating the theory of change on which the landscape approach is based

(ix) Principle 9: Resilience

Actions need to be promoted that address threats and that allow recovery after disturbances. Resilience may be improved through local learning and through drawing lessons from elsewhere

(x) Principle 10: Strengthened stakeholder capacity

People require the ability to participate effectively and to accept various roles and responsibilities. Such participation presupposes certain skills and abilities (social, cultural, financial). The complex and changing nature of landscape processes requires competent and effective representation and institutions that are able to engage with all the issues raised by the process.

¶ Forest Landscape Planning and Implementation

This section is based on: Implementing a Landscape Approach in the Agoro-Agu Region of Uganda, by J. Omoding, et al, 2020[2]. In this case, the Agoro Agu Landscape included the whole of NFA’s Agoro Agu Sector, which covers the four districts in the East Acholi Sub-region.

(i) Constituting the planning team

• Identify key stakeholders at the national, regional and local level and from public and private institutions and civil society. They may include forestry sector staff, private sector, CSOs, Central Government staff, District LG technical staff, political leaders, opinion leaders, etc.

• Holding an orientation meeting to introduce the team to the forest and landscape management planning guidelines, the general approach to be used, and training on participatory rural appraisal tools

(ii) Data collection and processing

Covers the entire landscape (district, sub‐county, parish, village levels), connectivity with agricultural land systems, wildlife conservation areas, wetlands, and other land use practices. Activities include:

• Designing tools including interview guides, focus group discussions, presentations to district and sub-county level meetings, planning matrices for environment action planning and forest resources evaluation and valuation matrix, timeline for tracking historical trends, and resource maps for each district

• Constructing a landscape planning knowledge base

• Conducting land use planning analysis using participatory rural appraisal and GIS

• Completing a social and strategic environmental assessment, and understanding the spatial-temporal changes.

• Data processing involving GIS experts, District technical staff, CSOs, political representatives, etc.

(iii) Developing actions based on an established vision

Participatory development of the framework Theory of Change for the landscape, through stakeholder engagements in each district and at the lower LG units

(iv) Development and validation of the Forest Landscape Management Plan

Members of the Planning Team are involved in writing the management plans based on the data collected and the framework Theory of Change. A number of plans may be developed from the data gathered: FMPs for the CFRs, and District Forestry Development Plans (including LFRs), Local Land Use Plans, and a Strategic Landscape Management Plan encompassing all the other plans

(v) Approval of Forest and Landscape Management Plans

The plans are approved in accordance with the legal provisions – NFA Board for CFRs, LG Councils for the other plans. The activities in the plans will then be integrated into the LG Development Plans.

(vi) Implementation of the Plan

Translate the 10 Principles of the landscape approach described in Section 3.6.2 above into activities on the ground. For more detail on the methods, see J. Omoding, et al, 2020 quoted above

Instruction 116: Forest management planning shall take the landscape planning approach. This approach shall apply to preparation of FMPs, District Forestry Development Plan (DFDPs) and Annual Work Plans. Regional Forest Officers and NFA Range Managers shall be the main lead actors in planning and implementation of the forest landscape management plans

¶ Forest Management Based on the Intended Main Product or Service

In managing forest landscapes, it is important that FMIs are clear about what the main final products or services will be, and thus, design the forest landscape management objectives accordingly. Other products and services can then be planned around the main products/ services as secondary products/ services. For example if the main final product of the natural forest component in the landscape is sawlogs for high grade furniture timber, the species chosen for restoration of the degraded/ deforested areas may be Afzelia, Khaya, Maesopsis, Tectona spp, etc. or a mix of these species. Secondary products/ services of the forest in the landscape may then be expressed in objectives that include management of the forest for biodiversity conservation, watershed services, carbon sequestration, non-timber forest products, etc.

Additionally, the objectives of management based on the products and services provide guidance on the management options and detailed activities, all geared towards the achievement of the desired products and services. For example, the objectives for a plantation component in the landscape will guide the selection or choice of a tree species to be grown, the method to be used (e.g. natural regeneration or planting seedlings), etc. The detailed management activities are usually based on the best practice and technical guidance for effective achievement of the desired products and services.

More specifically, urban and peri-urban forest reserves have previously been managed with the objectives of providing forest products like timber, poles, and firewood, among others. These objectives tend to target the urban and peri-urban low income earners. While these objectives are noble, the reserves will be more sustainable if they are also managed from the point of view of recreation and enhancing the cleanliness of the urban environment. Implementing such objectives will then accept physical structures that would normally not be readily acceptable in the FRs located in rural areas (e.g. restaurants, children play areas, facilities for wedding parties, etc.). This will cater for the low income segment of the urban population, but the high income segment (where major policy decisions are mooted and taken) will also recognise values that cannot be met by money alone. This will also generate much more revenue for the FMIs (mainly through presenting opportunities for small to medium scale business opportunities), than what is being earned from poles and firewood. Therefore there will be a need for focused restoration work in the urban and peri-urban FRs to provide for these objectives.

Instruction 117: The main management objective for urban and peri-urban FRs shall be recreation and providing a clean and healthy urban environment, with the associated objectives of education, research, biodiversity, clean water, and timber and non-timber forest products.

¶ Management of Forests for Biodiversity Conservation

Biodiversity conservation is the practice of protecting, preserving, and wisely using species, habitats, ecosystems, and genetic diversity on earth. It is important for our health, wealth, food, fuel, and services we depend on, and thus, biodiversity plays a crucial role in supporting economic growth and the general wellbeing of society at local, national, and global levels. Biodiversity conservation, together with other SFM practices reduce the amount of greenhouse gases (GHGs) released into the atmosphere.

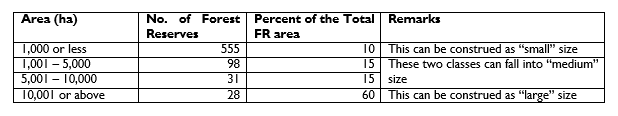

¶ Forest Biodiversity Conservation Master Plan

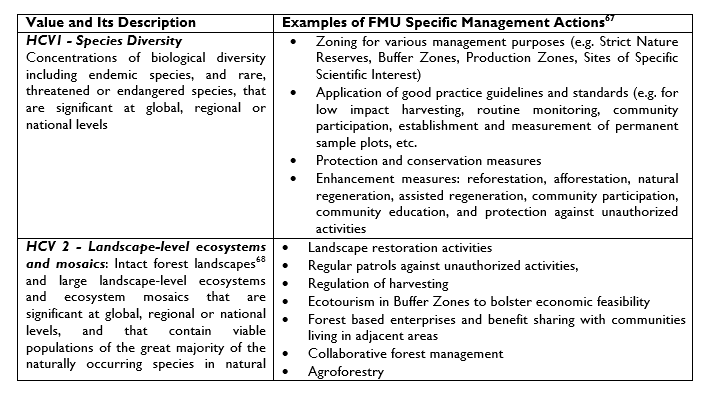

The Forestry Nature Conservation Master Plan, 2002 (FNCMP) provides for management of biodiversity, with particular focus on forests in PAs. The Plan has zoned the forest estate as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Areas of Strict Nature Reserves and Buffer Zones in Uganda’s CFRs

Source: Ministry of Water, Lands and Environment, Forest Department, 2002. Uganda Forestry Nature Conservation Master Plan, June 2002.[3]

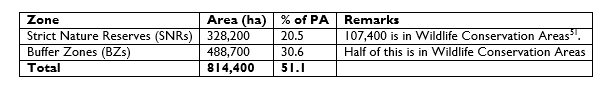

About 45 forests host the conservation sites. Eight are categorized as being of “prime conservation importance”, 11 of “core conservation importance”, and 26 of “secondary conservation importance” (Table 5)

Table 5: Areas Set Aside For Biodiversity Conservation in Uganda

Source: Uganda Forest Nature Conservation Master Plan, 2002.

Twenty-seven of the conservation forests have been categorized as sites of critical biodiversity importance by the FNCMP, and 57% of the conservation area (SNRs & BZs) is located in CFRs.

Management practices for the conservation sites have been elaborated in Chapter 4 of the FNCMP. Key among the provisions for each forest where conservation zones are located include:

(i) Development and establishment of locally-acceptable zones;

(ii) Roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in management decision-making and implementation;

(iii) General management procedures, including boundary demarcation, patrolling, community outreach, research and monitoring, ecosystem management;

(iv) Requirements for management of infrastructure and facilities;

(v) Specific requirements for Nature Reserve designation, demarcation and management;

(vi) Protection and management procedures for other conservation areas;

(vii) Conservation aspects of management within timber production zones; and

(viii) Institutional arrangements for implementation of the FNCMP.

Instruction 118: The FNCMP shall be reviewed and re-structured into a “Forest Biodiversity Conservation Master Plan” and kept regularly updated using Best Available Information, sourced from monitoring and evaluation activities of FMI work plans and projects.

Instruction 119: The provisions of the FNCMP have been translated into Programmes and Strategies in the NFP. The strategies shall be internalized in FMPs and DFDPs, which shall be the basis for preparation of annual work plans (AWPs) and budgets at national and District LG levels.

Instruction 120: In addition, the following actions should be taken into account in the management of forests for biodiversity conservation[4]:

(i) Before areas are designated as production areas, surveys shall be conducted to identify any high conservation values that are found in the area so that actions can be planned for their maintenance and/or improvement.

(ii) Retain as much of the natural biodiversity of any forest under management as possible in order to ensure the continued functioning of the forest ecosystem.

(iii) Where possible, create or maintain habitat corridors between blocks of forest to permit the movement of forest interior species including, e.g. creating buffer strips along water bodies, retaining canopy connectivity over roads and crossing points on roads, etc.

(iv) Ensure clarity of boundaries of local use areas and access rights for timber, non-timber forest products, fish and wildlife

(v) Studies of the ecology and habitat requirements of species of conservation concern should be incorporated in the management of production areas in tropical moist forests.

(vi) Patches of habitats with high species diversity or other special conservation values should be identified within tropical production forests and special measures taken to ensure the retention of these values.

(vii) Maintain unlogged buffer strips around fire prone areas.

(viii) Pre-logging inventories (stock maps etc) should identify and map species and assemblages of species of conservation concern, such as nesting and fruit bearing trees, and other important biodiversity features.

(ix) Protective buffer zones should be created along water courses of a dimension appropriate to the size of the watercourse and the nature of local topography

(x) Avoid the deliberate introduction of species that may be invasive and take prompt action to eliminate any populations of invasive species that may become established.

(xi) Manage plantations in ways that retain patches/strips of natural vegetation such as riverine forests, wetland forests, shrubs and thickets on steep hill slopes, etc., and manage them for production or provision of environmental services.

¶ Action Planning for Threatened/ Endangered Species

Uganda is blessed with a rich diversity of natural habitats, species and genetic resources in its forests. This biodiversity is also important to human health and wealth, for example by providing traditional plant medicines, wild relatives of domestic plants, a variety of ecosystems and species important in the tourism industry, and potential opportunities for Ugandans to adapt to local and global change. And yet, forest biodiversity is under threat from:

• Unsustainable harvesting, habitat conversion, the introduction of alien species and pollution;

• Illegal trade in plants and animals, including poorly regulated access to genetic resources;

• Poor forest governance which results in:

o Unprincipled giveaway of PA lands,

o Exploitation of forests arising from poor administration of the FMIs,

o Inadequate demonstration of the importance of biodiversity in the annual plans and budgets of FMIs

Threatened tree species in Uganda for which action plans are urgently needed include, among others[5], Albizia ferruginea, Aloe spp, Cordia millenii, Encephalartos spp (cycads), Entandrophragma spp, Guarea cedrata, Khaya spp, Lovoa spp, Milicia excelsa, Afzelia bipindensis, Beilschmiedia ugandensis, Calamus deerratus (rattan cane), Chrysophyllum spp, Citropsis articulate, Cola congolana, Dalbergia melanoxylon, Erythrophleum suaveolens, Fagaropsis angolensis, Olea welwitschii, Podocarpus latifolius, Prunus Africana, Tamarindus indica, and Vitellaria paradoxa. A more detailed list of threatened species in Uganda, and the geographical locations in Uganda, is contained in the Red List of Threatened Species of Uganda, 2018.

One of the pressing challenges facing biodiversity conservation, and by implication the conservation of threatened species, is how to balance the continued survival of biodiversity in the face of the political economy existing in the country. However, the Forestry Policy recognises that the current PFE contains most of the country's valuable biodiversity. The policy provides for gazetting of additional areas where these areas are identified as being of national significance for biodiversity conservation or protection of watersheds, riverbanks and lakeshores, and would be better managed as PAs.

Instruction 121: In Uganda, the IUCN Guidelines for Conservation of Species[6] can be used in one or more of the following key situations with reference to forest ecosystems and landscapes:

• A species has been observed to be declining in numbers

• New threats have appeared, and or existing threats are intensifying

• A significant habitat loss or fragmentation has occurred

• When a population is threatened by major disruption of its habitat or ability to carry on an undisturbed existence through a proposed major land use change, such as through infrastructure development

• During an ESIA or Social and Biodiversity Impact Assessment exercise

• When a population is subject to significant harvesting, whether legal or illegal

Instruction 122: Priority for species action planning undertaken by FPs should target the high furniture grade timber species. The action plans shall be included in the relevant FMPs and updated regularly as scientific information about the species continues to unfold.

The main pressures to threatened species populations are habitat destruction and the extraction of wild plants for timber, horticultural and collector trade. However, these actions are often influenced by the broader society where the demand for natural resources, through mining and agriculture, results in habitat destruction and the international trade in threatened species (often illegal) creates a demand for wild collected plants. The challenge for threatened species is to identify these forces and to develop and implement conservation strategies that will be effective within the context of these local, national, and international dynamics. To this end:

Instruction 123: Species action planning should be done early in the planning cycles so that it can feed into the main national and LG development planning frameworks. In a similar manner the activities in the Species Action Plan shall be incorporated into the FMPs, the DFDPs, District Environment Action Plans, and consequently into the AWPs of the Government FMIs

Instruction 124: Species action planning shall involve key stakeholders, including the relevant government institutions, Public Sector Organisations, CSOs, academic institutions, research institutions, and cultural institutions, among others

Instruction 125: The content of a species action plan shall take into account, but shall not be limited to the activities listed below. The actual content of the species action plan will then be guided by the amount of information that is available, the species focus for the action plan, and the resources (expertise and finances), among others

(a) Develop links with organizations focusing on biodiversity hotspots to maximize synergies

(b) Identify threatened species in accordance with the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1[7].

(c) Raise the planting material for ex situ species conservation in the nurseries, mainly from wildlings of the threatened species

(d) Plant them ex situ or as part of restoration of degraded forest areas

(e) Conduct an inventory of existing botanical gardens and arboreta

(f) Undertake the necessary studies to site arboreta/ botanical gardens and establish the institutional arrangements for them

(g) Strengthen existing gardens and arboreta and establish new ones

(h) Develop and implement a protocol for duplicate collections and exchange of material between gardens/ arboreta housing threatened species gene banks

(i) Review current trade (legal and illegal) and its impact on wild populations

(j) Facilitate sustainable trade in threatened species

(k) Develop a conservation culture among threatened species collectors and their promoters

(l) Survey threatened species populations

(m) Support the study on persistence of small populations and identify the key factors influencing decline and recovery

(n) Identify the best methods for the propagation and cultivation of species that are threatened by trade.

(o) Disseminate the results of existing and future research work on threatened species

More detailed guidance on species conservation planning may be obtained from the IUCN Guidelines for Species Conservation Planning[8].

¶ Threat Reduction Assessment for Measuring Progress in Biodiversity Conservation

For purposes of biodiversity conservation, a total of 66 CFRs in Uganda have been categorised as of Prime, Core, or Secondary conservation value. Some of the key activities prescribed for these CFRs by the FNCMP involve forest protection. Consequently, Government FMIs (especially NFA and UWA) have continued to prioritise forest protection in terms of resource allocation (budget, vehicles, and personnel).

In the foreseeable future, the NFA and UWA will continue to spend an appreciable amount of money on protection of natural forests, especially for purposes of biodiversity conservation and general ecosystem integrity. In addition, the performance of these institutions is going to be judged more and more through their achievements in protecting the natural forests in PAs.

On the other hand, the NFA has been working towards RFM which can be independently verified, eventually leading to international forest certification. However, a significant challenge has been how to specify indicators that demonstrate visible progress in effective protection of natural forests. Therefore in order to demonstrate specific results of forest protection, activities to establish and monitor specific threats to particular forests at FMU level is the subject of threat reduction assessment (TRA). The TRA is carried out at pre-determined intervals, depending on the degree of threats faced by a FMU.

Accordingly, NFA has developed a Field Manual for Threat Reduction Assessment. Using the Manual, the FP will be able to:

• Understand the importance of monitoring threats to natural forests at FMU level

• Design and carry out TRA at FMU level

• Develop a monitoring and evaluation framework for managing identified threats

The practical problem has been the difficulty of demonstrating in specific terms the results of the protection activities. The ultimate results of the TRA is a Threat Reduction Index. The index is developed by ranking each identified threat according to specific criteria, and assessing progress in reducing each of the threats. The Threat Reduction Index then aggregates the assessments of individual threats

The detailed field procedure [9] is provided in the TRA field manual available at the NFA. The manual was developed during a series of field training exercises that were based on Richard Margoluis and Nick Salafsky, 2001[10].

Although the procedure was developed with biodiversity conservation in mind, it can also be used for monitoring threats in production areas of natural forests.

Instruction 126: FMU staff shall use the NFA Field Manual to design TRA programmes for the relevant FMUs, which shall be used to monitor progress in achieving some of the biodiversity conservation objectives. The assessments shall be carried out at least once every two years and the results shall feed into the NFIMS (Section 9.9), and the monitoring and evaluation arrangements of the FMI (Section 10.10).

¶ Management of Forest Vegetation for Watershed Functions

The regulation of water quantity and quality is among the most important forest ecosystem services in Uganda. The Society of American Foresters (2020)[11] states that forests are a fundamental component of the hydrological cycle because they “capture, filter, store, and release water over time”. Tree canopies intercept rainfall and thus, reduce the speed and energy of raindrops that fall to the forest floor, and in the process protect the soil surface from water erosion. On the other hand, forest soils absorb large amounts of water that reach the ground, leading to recharge of underground aquifers. This water is then slowly released into streams, lakes, and rivers, providing a steady supply of water for production and human use. In addition, well managed forests filter surface runoff, and thus enhance the quality of water in the streams, rivers and lakes.

¶ Management of Forest Vegetation for Increased Water Yield

In general, water infiltration and retention are encouraged in forest soils by dense, deep root systems and a thick and porous organic top layer. Surface runoff is, therefore, minimal in forests and groundwater recharge is efficient, resulting in more consistent stream flows over time compared with any other land cover.

Instruction 127: To support this regulating function of forests, forest managers should identify the micro-catchment areas for important water sources in their jurisdiction and prepare catchment management plans (Module Two, Section 6.8) with the following possible activities, among others:

• Protect or restore vegetation cover (indigenous tree species mixed with shrubs and grass cover, as appropriate).

• Where there is compaction of soils (e.g. through overgrazing or movement of machines), adopt practices that loosen surface soils (e.g. deep cultivation, control of cattle numbers, and adoption of low impact harvesting methods (Section 3.1)

• Where agricultural crops are being grown, adopt agroforestry practices that maintain a high amount of organic matter in the soil, and improve soil structure, which helps increase water infiltration.

• Seek collaboration with the relevant staff and CSOs in the district (e.g. agricultural extension and community development)

Apart from total yield, the watershed manager is also concerned with when the increase comes. There may be specific times when downstream quantities are not enough for the needs there. It may also be necessary to maintain minimum quantities for upstream services.

Instruction 128: Therefore, adopt the treatments in the instruction above to augment underground storage so that there is enough water for dry season flows. Time vegetation removal with periods of maximum growth rates and not the dry season when there is no precipitation to seep into the soil.

¶ Management of Vegetation for Water Quality

Water from undisturbed forest is of the highest quality for downstream communities. As the water moves downstream through degraded forestlands, the quality of water tends to drop. This may be due to sedimentation arising out of soil eroded from upland, depending on physical and biological characteristics and land use. Good tree cover, with healthy undergrowth, is the most effective land cover for minimizing water sediments.

Instruction 129: Managing watersheds to prevent sedimentation means controlling soil erosion upstream. The activities listed in Section 3.5.2.1 above will also serve the purpose of maintaining and/ or improving water quality

Instruction 130: In forest management operations, road construction and logging cause most erosion. Therefore, during road building, minimise soil disturbance by avoiding stream channels, avoiding unstable soils, keeping gentle grades, minimising length and width, providing a buffer strip of vegetation between roads and the stream, completing particular sections in a particular season, providing adequate drainage and carrying out proper and timely road maintenance works.

Instruction 131: The disturbed areas should be stabilised by re-vegetation, stabilising the soil mechanically and surfacing the roads.

Instruction 132: During timber harvesting, the following precautions shall be taken:

(i) On steep slopes, exclude large machines that skid logs on the ground.

(ii) On very steep slopes, logging should be prohibited or where it is inevitable, conversion should be done at the felling site.

(iii) Logging by ground machines should be planned in such a way as not to skid directly down-slope or through stream channels.

(iv) Selection felling systems are preferable to those tending towards clear-felling.

(v) Only light selective felling should be allowed near stream channels leaving a stretch of undisturbed forest as a buffer for the stream.

(vi) Logging debris should be removed from streams.

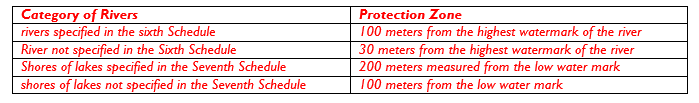

Instruction 133: Herbicides, arboricides and pesticides may add chemicals to water bodies if they are not carefully applied. Therefore, avoid the use of chemicals as much as possible. Otherwise, leave the statutory protection zone widths of 30-200 metres of untreated vegetation depending on the type of water body (Table 6)

Table 6: Protected Zones for Water Bodies

Source: The National Environment (Wetlands, River Banks and Lake Shores Management) Regulations, No. 3/2000 – 6th and 7th Schedules

Instruction 134: Riparian buffer zones should not be harvested for timber, and management should aim to minimize disturbances in them. Degraded riparian buffers should be restored to ensure good water quality.

Instruction 135: Cool temperatures are good for water for human consumption and a good fish habitat. Therefore, keep shade producing vegetation beside stream channels and watering points

¶ Management of Forests for Flood Control

Forest soils act as sponges and retain water longer than soils under other land uses. Forests hold soil in place by the roots of trees and the associated vegetation, provide additional water storage capacity underground, promote high infiltration rates and ultimately, they minimise erosional sedimentation which has an effect on stream discharge capacity. Tree and forest removal, therefore, increase water discharge and the risk of flooding in rainy seasons and the risk of drought in dry seasons. Reforestation and afforestation have the opposite effect on water quantity. The effects of forest management for flood control are most prominent at the micro level and for short-duration and, therefore, need to be integrated into other soil and water conservation measures.

Instruction 136: The following measures may be applied depending on the forest conditions:

(i) In steep headwater watershed areas, natural vegetation should be kept in place and, if harvested, harvested selectively. This then excludes farming and minimises grazing. Otherwise, strict soil conservation measures must be put in place.

(ii) If fire must be used for management purposes, it must be kept light. Peak water run-off flows become more destructive when they carry large amounts of debris left by fierce fires.

(iii) A lot is achieved through careful logging and road construction practices that minimise soil disturbance.

(iv) Re-vegetation of severely degraded lands restores vegetation in uplands that have been denuded by over exploiting forests. In severe cases, re-vegetation may be combined with mechanical soil conservation measures. To allow the cover to establish, other vegetation types should be established to quickly check soil erosion. In non-reserved forested areas, the locally resident communities should be fully involved in preparation and implementation of management plans.

(v) Forests are effective in minimizing surface erosion for a range of reasons. For example, their canopies, undergrowth, leaf litter and other forest debris reduce the impact of rain drops on bare soils, their porous soils help infiltration thus reducing surface water flows and their root systems help hold soil particles together.

(vi) Forests can also help stabilize slopes and protect them from shallow landslides. Landslide-prone areas should be kept forested (or maintained as woodland or agroforestry/silvo-pastoral systems with high tree densities) to reduce the occurrence and severity of shallow landslides. Tree-harvesting activities in such areas should be light and non-mechanized. Note that although forests can play an important role in soil stabilization, there are cases and sites where they will not prevent or mitigate landslides caused by tectonic movements.

¶ Management of Mountain Forests

Mountain forests have a close association with freshwater as they gather water not only through normal vertical precipitation (rainfall) but also by “water-stripping” the fogs and clouds that move horizontally through them. Mountain forests (sometimes also called fog forests) are, therefore, important for water production. Trees can be planted in strategic cloud and fog locations to maximize water-stripping. Mountain forests show a complex relationship between flora, fauna and soils and their loss is irreversible.

Instruction 137: Given their importance in water production and biodiversity conservation, and their general unsuitability for other uses (for example because of soil limitations and climates that are often unfavourable for agriculture), mountain forests should be maintained as forests and identified in national inventories.

¶ Management of TMFs for Forest Products

The National Forest Plan (NFP) focusses on promoting the development of the products and services which have high contribution towards accelerated national social-economic development including high grade timber, construction and industrial poles, woodfuel, non-timber forest products like rattan, herbal medicine, bee products, fruits, ecotourism, aromatic oils, and water catchment services, among others[12].

Apart from timber and industrial poles, the other products and services come mostly from natural forests (TMFs and OWLs), especially from PAs. It is, therefore, important that natural forests are managed in a responsible manner so that they can continue to provide these products for a long time.

NFA has developed a technical guide to support management of Uganda’s TMFs for timber production in CFRs for the purposes of ensuring sustainable management of production zones of TMFs (NFA, 2006)[13]. The guide goes into more detail regarding production of high-grade timber and provides for participation of forest dependent communities in accessing meaningful benefits from the forests. The Natural Forest Management Strategy has outlined six strategies and 40 actions for CFRs[14].The strategies and actions are presented in Annex 7.

¶ Management of TMFs for Timber Production[15]

Timber production in natural forests will normally be possible mostly in well-stocked TMFs. Since virtually all existing TMFs outside PAs in Uganda are highly degraded or completely depleted, and those in Conservation Areas are not available for harvesting, it will only be possible to produce timber from production zones of TMFs in CFRs. Even here, it will be limited to the few CFRs where it can be demonstrated through EI that they are well stocked (adequate basal area).

Increasing pressure on land is leading to increased demands to release more natural forests (in PAs and outside) for agricultural production. An important factor in countering this pressure is to show that the natural forests are being managed for economically viable production of products and services through conspicuous forest management activities. Thus:

***Instruction 138: Management practices for production zones of natural forests shall demonstrate:

(i) Increasing revenues raised from high quality and well stocked natural forests.

(ii) Development of forest-based small and medium scale enterprises.

(iii) Increasing employment of local people.

(iv) Discouragement of illegal activity by constant presence of staff and licensees in the forest.

It is vital to ensure that the forests are managed in a way that optimizes high quality products and services which are not readily produced from plantations. This calls for affirmative silviculture rather than laisez faire management, which is advocated for in large forest tracts elsewhere in Africa and other regions. Failure to observe this will perpetuate the problem of a forest where selective felling of the best trees and species leads to an ever-increasing proportion of defective trees and species that are cheap on the market.

Instruction 139: The Forest Improvement Management System shall be the main vehicle for managing natural forests in Uganda. Central to this System is EI, ISSMI, and PSPs, which generate information that enables forest managers to use low impact logging techniques.

The Forest Improvement Management System has the following features:

(i) A felling cycle of 30 years, but should the managers want to change, the system is flexible enough to adopt different felling cycles.

(ii) Harvesting is controlled through an Annual allowable cut that varies from forest to forest, but averaging 25-30m3 or basal area of 3-4m2/year or about 1m3/ha/year. The felling series are based on the management plan period of 10 years.

(iii) Each felling series is divided into 10 annual felling coupes, the period of a normal FMP.

(iv) Felling intensity can vary depending on the forest manager’s needs. But intensities will be higher where affirmative silviculture is planned.

(v) Reduced impact logging systems in which the largest machinery permitted in the forest are agricultural tractors or light skidders. Therefore, common harvesting systems include small mobile sawmills or pitsawying.

(vi) It provides for effective monitoring of progress in harvesting at block level.

(vii) Tree felling is done for economic and silvicultural reasons.

(viii) The activities of management inventory, stock survey and diagnostic sampling are integrated into one operation. But sometimes it will be necessary to assess regeneration performance at intervals that are shorter than the felling cycle.

(ix) Cyclic management inventories enable the forest manager to track forest performance.

(x) The physical infrastructure in the forest (block lines & strip lines, corner trenches, block labels) are maintained for after-harvest, in-forest activities.

(xi) It encourages forest management staff to spend quality time in the forest implementing technical activities. In the process, reduced illegal activities becomes a positive impact rather than remaining a focus activity. Consequently, financial and human resources are more efficiently and effectively utilized.

(xii) Provides possibilities for licensing forest dependent communities to harvest sawlogs in small quantities, which they can afford without excluding the larger, more commercial operations.

Instruction 140: The principal operations in the Forest Improvement Management System shall include:

(i) Conduct of a more detailed ESIA than the one done for the whole FMP

(ii) EI (Section 3.4.1) to establish the 10-year felling series, annual felling coupes, and Annual allowable cut

(iii) Forest Management Planning.

(iv) ISSMI (Section 3.4.2) to establish the trees to be harvested, those to be reserved for seed, and those to be allowed to grow for harvesting during the next felling cycle tree.

(v) Timber harvesting following the ISSMI tree maps and list of stock trees to be harvested (Section 3.4.2).

(vi) Assessment of natural regeneration (Section 3.4.7) to establish the actions that should be done.

(vii) Carrying out actions that are necessary for development of a good future crop (e.g. climber cutting, felling damage repair, spot planting or only monitoring regeneration performance)

¶ Management Cycle for Timber Production in Natural Forests

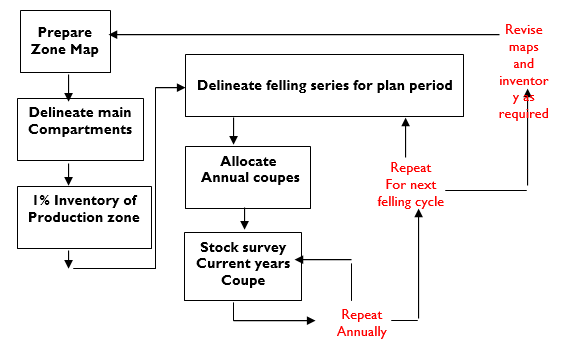

Instruction 141: On the basis of the Forest Improvement Management System the timber harvesting cycle in TMFs shall be 30 years, employing the reduced impact logging system. The cycle is shown in Figure 6. Accordingly:

• Where zoning for biodiversity conservation is desirable, the forest shall be zoned on a map and on the ground

• EI, the Point-Centred Quarter Method (Section 3.4.5 above), or some other method that can produce similar results shall be used in the production forest to establish the products which forest management shall work towards

• The felling cycle for each of the woody products shall be established through research. For timber production in TMFs studies have established a felling cycle of 30 years using a selection felling system[16].

• A FMP shall then be prepared in a participatory manner (Section 7.7.2). The FMP shall show different felling series, annual coupes which should also be clearly identifiable on the ground (compartments, felling coupes, etc)

Figure 6: Timber Harvesting Cycle in the Tropical Moist Forests

Source: NFA, 2006. A Guide to The Management of Uganda’s Tropical Moist Forests for Timber Production

¶ Management of Other Wooded Lands

The main management objectives of OWLs will normally not include timber (although it should not be excluded), but the products are likely to include charcoal, firewood, and bee products, among others.

¶ Division of the Forest into Compartments

Instruction 142: For ease of management, the forest should be divided into smaller areas known as compartments. To divide the forest into compartments:

a) As much as possible, physical features like roads/paths, streams, valleys, and ridges, shall be used to form natural divisions. Otherwise, other relatively permanent features may be used, e.g. areas characterised by a dominant vegetation type. In such cases, the compartments shall be delineated by cut lines.

b) A general guide for compartment size is 100ha, but smaller or larger sizes may be adopted depending on the size of the forest, variability in terms of physical and vegetation features, ease of access, etc.

¶ Inventory of growing stock

This has been described in Section 3.5.5 above and Annex 6

¶ Development Towards a Closed Natural Forest

Forest Department experiences from the 1950s indicate that most areas had been prevented from developing to closed natural forest (e.g. Kitigo Block in Budongo CFR) because of fires. Many of these areas stop at the fire climax but if fire is excluded, they can develop to closed natural forests over time. This development can be assisted by enrichment planting as was demonstrated in Matiri and Opit CFRs (Petero Karani, 2006[17]).

Experience has shown, however, that the quickest means of getting THF colonisation is to establish mixed hardwood plantations of indigenous species first, and THF species will invade the plantation as soon as the grass has been suppressed. This has been the case in Kibale Forest, areas of Matiri CFR, and Namaganda Hill in Mabira CFR.

Instruction 143: Where it is desirable, especially for purposes of biodiversity conservation and other High Conservation Values, OWLs shall be managed in a way that facilitates their development towards closed forest. Constant fires and grazing (often acting together) are the commonest factors that prevent an area from developing into a closed forest. Therefore, where this is a management objective, management activities shall include protection from fires and grazing.

However, complete protection from fires might be difficult over the medium to long term. And yet if protection is successful for only a few years, a substantial amount of dry grass and leaves (fuel) accumulates, and thus an accidental fire entering that area can be very destructive.

Instruction 144: To prevent such unfortunate accidents, early controlled burning should be done periodically to burn off the grass/ leaves before they can accumulate to dangerous flammable levels should a fire break out. Controlled burning shall take into account the following considerations:

• All neighbours to the area to be burnt should be given adequate notice of the exercise

• Firelines should be cleared around the area to prevent fire from getting out of control

• Adequately trained personnel shall be deployed in sensitive areas like settlements and plantations

• The windward sides of hills normally dry out earlier than the leeward sides

• Areas with a large accumulation of dead material will burn earlier and more fiercely than those with less dead material

• Grass growing on shallow soils will normally dry out and be ready for burning earlier than grasses on deep soils

• Fire moves more quickly uphill than downhill. Therefore, in the earlier days of the controlled burning exercise, when the grass still retains its green, it is advisable to start burning uphill, but later, when the grass is drier, burning can start on the upper slope in order to avoid the fire getting out of control

• Burning should start around mid-day early in the burning season, and progressively start earlier as the activity moves into the drier period.

¶ Managed Charcoal Production in Other Wooded Lands

Instruction 145: For most OWLs, charcoal burning goes on in an uncontrolled manner, and therefore the owners do not get much income from the operation. In order to bring charcoal burning under control, the following broad procedure should be followed:

a) Convene a meeting with the local people to inform them of what you are going to do. During the meeting, discuss:

• The people to be authorised to burn the charcoal

• What they must do or not do to ensure successful re-growth (fire protection, exclusion of grazing, etc.)

• Availability of seasonal contracts for carrying out activities like planting, patrolling, firelines, etc

• Any other matter of concern to the people

b) Divide the area into compartments using physical features as described in section 3.5.4.1 above, remembering that you will be back in this compartment in 10-15 years’ time. If the compartment is too large to be harvested by one authorized entity in one year, divide it into smaller blocks which you can allocate to different charcoal burners.

c) Carry out a reconnaissance of each compartment to determine the degree and quality of stocking of timber and other trees. The Point-Centred Quarter Method outlined in section 3.5.5 above is particularly good for this purpose.

d) Do not burn charcoal in a compartment with stocking of at least 18 trees/ha (10 cm + dbh) of good timber species. Such a compartment should be managed for woodland improvement (protection from fire and grazing, assisted regeneration, liberation tending of seedlings and saplings).

e) For the remaining compartments, decide on the order in which you will carry out charcoal burning (felling series). The aim is to move from one compartment to another in an organized manner so that by the time you complete the cycle and come back to the first one, the coppices will have grown to charcoal producing size.

f) In the compartment to be harvested for charcoal, mark all good quality timber trees so that they are not burnt into charcoal (e.g. Mvule, mugavu, nkalati) together with the other trees

g) Make sure you observe the legal requirements for protected zones as described under section 3.5.3 above

h) Put in place measures to protect the area from grazing and fires. The measures include:

• firelines towards the end of the dry season;

• patrols against grazing and fires;

• setting light fires through the area to avoid accumulation of dry grass that would result in hot fires in case of accidental fires; and

• where possible fencing off the area

i) Start harvesting the compartment/ small block by systematically clear-cutting from one side to another, but do not cut the good timber species as you progress.

j) At the onset of the next rains, examine the harvested area to assess the degree of re-growth (natural and coppices) with a view to filling in with more charcoal or timber producing seedlings. Diagnostic sampling tools should be applied for this.

k) From time to time, monitor progress of the re-growth, liberating it from climber tangles where necessary.

¶ Management for Firewood Production

Instruction 146: Generally, the process described for charcoal should also be followed for firewood production. It must be noted that firewood from natural forests does not fetch good money because in most cases, the market is limited to comparatively short distances from the forest if the trader is to make a profit. This shall be taken into account when a decision to manage the area for firewood is being taken.

¶ Management for Other Forest Products and Services

Instruction 147: Other forest products in this case include rattan canes, wild coffee, Gum Arabic, Shea Butter nuts, Prunus bark, honey, and crafts, among others. For most of these, there are no specific formal practices which have been developed so far. As the practices are developed, they shall be added to the manuals and field tools.

¶ Management of Dual Management Areas

Dual Management Areas are sections of FRs that are also gazetted as part of wildlife conservation areas. During the zoning of conservation areas in FRs, the Forestry Department decided that the Dual Management Areas shall be managed as Strict Nature Reserves or Buffer Zones, allowing only non-harvesting activities.

Instruction 148: Dual Management Areas shall continue to be managed as Strict Nature Reserves or Buffer Zones in collaboration with UWA. Details of how the collaborative actions at the FMU will work shall be discussed with UWA and included in the Memorandum of Understanding between the two institutions (Section 9.2.6).

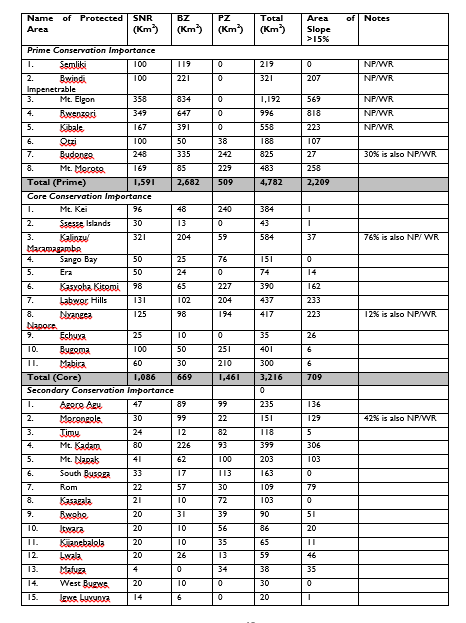

¶ Management of Forests for High Conservation Values

High Conservation Values (HCVs) are defined as biological, ecological, social or cultural values of outstanding significance at national, or regional or international levels[18]. Forestlands which have these values need to be managed well in order to maintain or enhance them. Example of management actions that can be implemented in the HCVs are outlined below.

The methods for managing HCV forests include identification, assessment, management strategies, implementation, monitoring, and then revisions of management strategies in line with monitoring results. (FSC, 2017 ibid). FSC has issued a detailed procedure for management of HCVs[23], and Annex I of the NFSS presents the HCV Framework for Uganda which domesticates the HCVs.

Instruction 149: The Ministry responsible for forestry shall regularly review (at least once every five years) the NFSS HCV framework in Annex I of the NFSS, using stakeholder participation methods, in line with the FSC Guidance for Developing National High Conservation Value Frameworks[24]. To this end the Ministry shall domesticate the FSC Guidance so that FPs can easily use it.

Instruction 150: FPs at FMU level shall identify HCVs that are applicable to their areas, and manage them in line with the FSC High Conservation Value Guidance for Forest Managers, and the provisions in the HCV Framework in Annex I of the NFSS. To this end, actions to manage the HCV forest areas shall be identified and included in the FMP, and subsequently, the AWPs.

¶ Management of Forest Plantations

This section deals with management of commercial timber[25] plantations and woodlots for small poles and fuelwood. The practices for growing the common species (pines and eucalypts) on a commercial scale have been described in detail in Jacovelli, et al, 2010[26], and for the small scale community tree growers the practices have been described in Sawlog Production Grant Scheme, 2011[27]. Practices for growing the other tree species are presented in Section 3.5.7 below. Jacovelli et al point out that production of fast growing and high yielding tree crops requires:

• Advance planning and budgeting

• Good matching of species to the sites

• Adequate and timely land preparation so that planting can be done early during the rainy season

• Use of improved seed and high-quality planting materials

• Good weeding before and after planting

• Using the correct spacing

• Timeliness in, and quality of planting and weeding

• Replacement of dead seedlings within the same planting season

• Effective protection from animals and fires

• Effective control of farmers if agricultural crops are grown among young trees

• Monitoring for pests & diseases

• Carrying out the other tending operations (e.g. thinning and pruning for timber) in a correct and timely manner

• Avoiding conflicts with neighbouring communities

Instruction 151: The Tree Planting Guidelines should be followed in growing timber plantations. The Guidelines shall be revised by FSSD periodically as new information emerges from experience and research. The Community Tree Planting Guideline prepared by the Sawlog Production Grant Scheme meets the needs. For the small woodlot growing by communities,

¶ Management of Coppices

The content in this section is adapted from:

• Sawlog Production Grant Scheme, 2005.Plantation Guidelines, No. 21. Sept 2005: Managing Eucalyptus Coppice; and

• Liz Hamilton, Colac, 2000. Managing Coppice in Eucalypt Plantations, June 2000: State of Victoria, Department of Primary Industries

¶ Introduction

Eucalypts has the ability to regrow from cut stumps (coppicing). Coppice management involves selection of suitable stems from this regrowth and the removal of all the others. Coppicing allows the grower to have a second crop without replanting. Only plantations that have not been thinned can be coppiced so that there are enough strong stools to regrow. Hence only stands grown for fuelwood and poles can be coppiced profitably. The ability of eucalypts to coppice declines with age. The larger more vigorous stumps of up to about 30 cm diameter, and from young trees tend to coppice best. Older stumps often fail to coppice.

The cut stump will normally put out many new shoots within a few weeks of being cut. If all of these shoots are left to grow, the stump develops into a bush crowded with multiple shoots. So it is necessary to choose specific stems according to their size and position on the stool and to remove the rest. This allows the remaining shoots to grow well and with a good form, giving the best yield.

Generally, planted or direct seeded plantations can be satisfactorily coppiced many times over. However, not all cut stumps produce good coppices, and over a number of rotations there will be a progressive decline in the number of live stumps which are able to coppice. From the first coppice, the rate of shoot growth from the rootstock can be expected to be around 10-20% faster than that of the original trees. However, the vigour of the coppice from subsequent crops tends to decline. Hence, it may be better to re-plant the site with seedlings after 3 or 4 rotations.

However, it is important to note that not all tree species will coppice after being cut. Some species which coppice include Calliandra calothyrsus, Cassia siamea, Cassia spectabilis, Eucalyptus spp., Leucaena leucocephala, and Markhamia lutea, among others. Certain species coppice well when young but may not do so if cut at maturity. Examples these species are Casuarina spp., Grevillea robusta, Sesbania sesban and some Albizia spp.

¶ Procedure for Coppicing

Instruction 152: To achieve the best possible results from coppicing, tree felling should observe the following:

(i) Trees should be cut at a slight angle to allow water to easily flow off the stump, and thus prevent decay.

(ii) Trees should be cut as low to the ground as practical. Coppice growth on high stumps tends to be weak and is more likely to be snapped off in strong winds. Coppice shoots originating near ground level will eventually develop into trees almost as well rooted as those of seedling origin. Therefore, aim for a stump height of no more than 15 cm.

(iii) Felling shall be done with a bowsaw or chainsaw. Felling with an axe damages the bark where the coppice grows from

(iv) Felling shall be done in blocks so that the coppices in one block can shoot at the same stage. Felling at random results in some stumps coppicing under shade and not developing, and also when the other trees are felled they damage the coppice.

(v) All felling debris shall be removed from the stumps

(vi) Care should be taken not to damage the stumps by driving over them or knocking them with poles.

Instruction 153: Dense coppice shoots usually appear within a few weeks of the tree being felled. Therefore, it is important to take stock of the stumps which are coppicing successfully. A general guide is that if less than 75% of the stumps are coppicing, replanting should be objectively considered, if the trees are being grown as a business.

Instruction 154: To optimise wood production on the most vigorous and healthiest stems, the number of stems should be thinned progressively:

a) The first reduction should be carried out when the dominant shoot height is 3 to 4m. 2 to 3 stems should be retained per stool.

o The selected stems should be dominant, reasonably straight, firmly attached (preferably from low down on the stool) and well-spaced out around the stool. This reduces the likelihood of a strong wind breaking off all the stems.

o The unwanted stems and other regrowth from around the stool must be cut as close to the stool as possible without damaging the selected stems.

b) The second reduction should be carried out when the dominant shoot height is 7 to 8m.

o Generally one stem should be left per stump but 2 stems may be left on the large stools adjacent to gaps or dead stumps. This is to maintain the stand at the original number of stems per hectare. The stems should also be similar in height so that the stand is uniform.

o 2 or 3 stems may be left along the edge of the stand (along roads and fire breaks). These stools receive more light and water than those inside the plantation and can thus support more stems.

c) Both the 1st and 2nd reduction operations create a lot of trash, which soon constitutes a considerable fire hazard. Hence the trash should be stacked tightly in every 5th row, with gaps 5m wide along each row to allow access. Also no trash or trash line should come closer than 5m to the edge of the stand.

d) As with any young trees, the young coppice needs to be protected from animals and fires. Insect attack should also be carefully monitored in the young coppice especially over the first 3 years.

¶ Silviculture of Selected Tree Species, Other Than Pines and Eucalypts

This section provides guidance on the practices which FPs may use to grow species that meet their tree growing objectives. The practices for Tectona grandis (teak), Gmelina arborea, Maesopsis eminii, Markamia lutea, Khaya grandifoliola, Khaya senegalensis, Melia Volkensii, and Melia Azedrach are summarized in Annex 8. However, there is still need for research in the growing practices in specific areas and management regimes.

Instruction 155: The practices described in Annex 8 should be used with a view to adapting them to the specific growing conditions (ecological and social).

Instruction 156: Studies shall be undertaken by government FMIs to update these practices as experience and knowledge emerges. Likewise, as demand for other species grows, the list of species shall continue to be updated.

¶ Tree Pests and Diseases

¶ Common Pests and Diseases

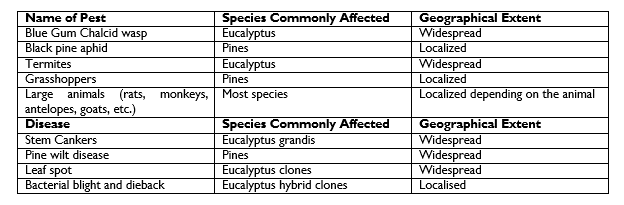

The pests and diseases which are common for the main timber plantation species in Uganda are presented in Table 7.

Table 7: Common Pests and Diseases in the Main Timber Plantation Species

Source: Jacovelli, et al, 2004: Tree Planting Guidelines for Uganda. Sawlog Production Grant Scheme

¶ Managing Forest Pests, Diseases and Damage

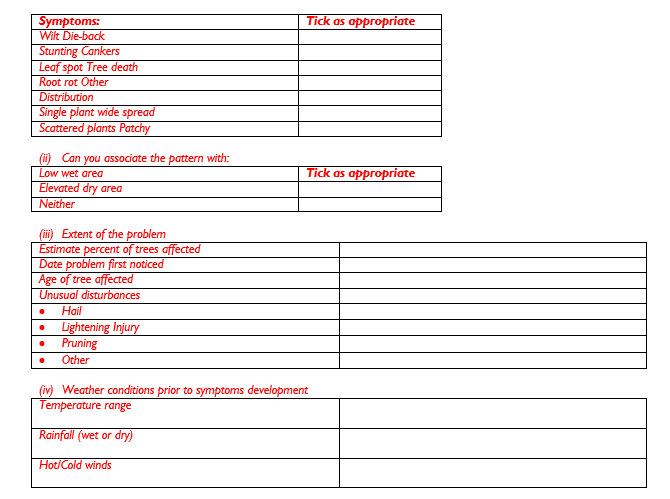

Section 36 obliges the Minister, NFA and District Council to notify the public about any pests and diseases that are dangerous to forests and forest products and to prescribe measures for control and eradication of the same. Regulations 50 – 58 provide for management of pests and diseases in forests and forest products. For this to happen FPs need to know how to recognise common pests and diseases and report them accordingly.

In recent times, Uganda, has experienced pests and diseases, especially in the single species tree plantations that have led to economic losses to tree growers. Prevalence of pests and diseases is expected to increase with climate change. It is therefore important that FPs can recognize and control the pests before they can cause widespread damage to forests and the products therefrom.

In the Field Guide for Recognition, Identification and Management of Pests and Diseases of Commercial Tree Species in Uganda, NaFORRI has described methods which can be used to identify and manage pests and diseases of commercial plantation trees. The Guide[28] has also outlined the procedures which can be followed by FPs if there is an outbreak of a pest or disease.

The insects and diseases have been categorised as defoliators, sap suckers, gall forming insect pests, shoot boring insect pests, stem boring and cutting insect pests, and root feeders. For each of these categories, the Guide goes in more detail examples of common insect pests, where they have been reported in Uganda, the hosts (tree species commonly attacked), description of the insect (how to recognise the insect), symptoms of attack, the damage they cause, and the control/ management measures.

The Guide also provides guidance on how to recognise diseases that commonly attack trees, especially in plantations, and how to control/ manage them.

Instruction 157: All FPs, especially at FMU level, shall be responsible for the prompt reporting of pests and diseases and other damage in the course of their work, using the guidelines from time to time issued by NaFORRI. All entomological and mycological reports and specimens shall be sent to NaFORRI, with copies to the FMI Headquarters using the report format below.

Name of collector: ………………………………………………..

Company/ Institution …………………………………………….

Physical Address: ………………………………………………..

Telephone no: ………………... Email: …………………………………..

Location where disease/pest is occurring and dates

GPS location: ………………………………………………………….

Village: ……………………….. Parish: …………………………………

Sub-county County ………………………………… District …………………………………….

Estate/ Forest: ………………………………………….. Compartment no: ………………………

Soil type: …………………………………………………………………

Date sample collected: ………………………… Date sample dispatched: ………………………

Type of sample

Soil Twigs …………….. Stems Water …………… Roots Insects ……………………

Leaves/needles ………. Seedlings/cuttings ………………… Other ……………..

Pest/disease description and history

(i) Tree species affected ------------------------------------------------------------------------

(v) Additional information (e.g. on control actions taken, etc.), if any:

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Name of Collector ……………………………………. Signature …………………………………..

Title …………………………………………………………………………..

Instruction 158: Collection and packing of insect specimens shall be handled as follows:

(i) Beetles – Place specimen in test tube or bottle and add spirit such as Ethanol (80%), pack in specimen tubes with most of the spirit poured off; if possible, seal the corks with wax.

(ii) Moths, flies, wasps - kill by fumigation with cyanide or, in emergency, petrol vapour. Pack dry in paper envelopes and include some naphthalene (moth balls) crystals.

(iii) Larvae - in Spirit. If possible, gently boil in water and allow to cool first.

(iv) Wood samples with living larvae - pack in tin or galvanised iron containers for reference.

(v) Collection and packing of fungal specimens shall include:

• Wood samples with mycelium - allow to dry on the surface before packing in wooden or metal boxes. The samples shall be wedged or enclosed in shavings to prevent movement in transit.

• Fruit bodies - dry slowly (not in direct sunshine) before packing in soft material enclosed in box. If possible, send the fruit body still attached to the host.

(vi) If it is not possible to get the chemicals and materials mentioned above, consult NaFORRI.

¶ Integrated Pest Management

Tree pests and diseases are limiting factors in tree nurseries and forests and should therefore be controlled well before they can cause economic damage. The most effective way to deal with forest pests is applying integrated pest management. Integrated pest management involves applying a combination of control options that include preventive, observational and suppressive measures to manage the pests. In applying integrated pest management, non-chemical methods such as cultural, physical and biological control methods shall be given priority but use of chemicals may be preferred as an alternative in severe cases where the pests can only be economically brought under control using pesticides. Refer to the Guideline for Tree Nursery Management for details on pests and disease management[29].

Many pests and diseases can be prevented when species are correctly matched to the sites where they are grown. This avoids stress, which weakens the resistance of the trees. Secondly the pests and diseases can be avoided by carrying out proper cultural operations like weeding, avoiding water logging, etc. Nevertheless, when symptoms of pest or disease attack are first observed (e.g. unexplained death of a tree or groups of trees, swellings on the stem, exudates, dieback, unexplained growth defects, etc.) by the tree grower, it is advisable to seek professional advice from the National Forest Resources Research Institute.

Instruction 159: FPs shall, as a priority, show commitment to reduction and eventual elimination of chemical usage and adoption of integrated pest management practices due to disadvantages associated with chemicals. The integrated pest management methods will include[30]

• Preventive silvicultural measures – which include use of healthy quality planting materials (free of pests and disease); raising healthy seedlings which are vigorous; maintaining a clean nursery environment that reduces the risk of pests and diseases;

• Monitoring through regular observations to identify any signs of pests, such as termites, ants, cutworms, or diseases (fungal, viral and bacterial);

• Mechanical control, which involves physical removal of the pests e.g. digging up anthills;

• Application of organic pesticides and fungicides (Section 3.5.8 below);

Instruction 160: The first line of defence against pests and diseases of planted trees shall be to match the species to the ecological conditions of the site where it is proposed for planting. If the two match, then the second line of defence is to effectively carry out all the appropriate silvicultural and tending operations. This way the plants will be provided with growth conditions that do not stress them and thus weaken their natural ability to resist pests and diseases. Nevertheless, when the pest or disease is first noticed, it should be reported to the Entomology Section at NaFORRI for a more focused assessment.

¶ Use of Chemicals to Control Pests and Diseases

Where non-chemical methods fail to work, chemical pesticides are often used. A wide range of chemicals are used to suppress weeds or prevent/ treat pests and diseases. The chemicals work through their toxic properties, but if they are not used properly, they may also be harmful to people, wildlife, and the environment in general.

Instruction 161: The pesticides used shall not be categorized as highly hazardous or hazardous pesticides by the Forest Stewardship Council A.C (FSC Pesticides Policy, 2019[31]). They should also not be listed in Schedule 8 of the National Environment Management Act, 2019[32]. If chemicals are used, then forest workers must be properly trained, should wear the prescribed PPE during spraying operations, and adhere to environmental precautions.

Instruction 162: Many of the chemicals used in forestry work may be toxic to human beings e.g. insecticides, fungicides, herbicides and preservatives. It is important for both FPs and workers to ensure safety against the application of such materials. In particular, the FP shall provide hands-on training of the workers and assess their competence in the proper use of equipment and application of chemicals. When using chemicals, workers must take into consideration the following safety rules:

(i) Use only under the supervision of a responsible person.

(ii) Follow the manufacturer’s instructions closely.

(iii) Wear coveralls and rubber gloves or barrier cream. If applying or mixing powders, a face mask or goggles is necessary.

(iv) Wash off using soap immediately any chemical falls on the skin.

(v) Wash thoroughly using soap after using toxic chemicals, and before eating or smoking.

(vi) Destroy or render unusable all chemical containers and do not let them be used for carrying drinking water.

(vii) Keep all chemicals in a safe place and under lock and key.

(viii) Members of the public must be warned if they are likely to visit an area where toxic chemicals have been used. Do not use toxic chemicals where domestic animals are likely to wander, or near water supplies.

Instruction 163: The checklist below should guide the FP in order to achieve effectiveness and efficiency in the use of chemicals[33]:

(i) Identify the target weeds so that the correct herbicide and dosages can be used

(ii) Buy only good quality spraying pumps, whose spare parts can easily be obtained within the country

(iii) Buy chemicals from reputable dealers and only accept sealed containers with the original manufacturer’s label on.

(iv) Read the manufacturer’s prescriptions on the label carefully before using the chemical

(v) Ensure the correct pump nozzles are used for the job in hand

(vi) Time the operation so that the target weed is at the right stage of development for cost-effective treatment

(vii) If pre-plant spraying with Glyphosate, time the operation so the spraying operation is carried out as close as possible to when the site will be planted

(viii) Regularly calibrate equipment and spend time training a spray-team

(ix) Spray operators must wear coveralls, gumboots and other appropriate protective equipment at all times

(x) The pumps must be regularly inspected for leaks and to ensure that they are in good working order

(xi) Spraying must only be carried out under favourable weather conditions.

(xii) Spray operators must be provided with clean water and soap for washing with on site

(xiii) The herbicide containers must be properly (and securely) stored, and empty ones punctured and disposed of properly to prevent re-use for other purposes

(xiv) Any undesirable effects observed during or after the application of herbicide should be appropriately mitigated

(xv) The application of chemicals must avoid the risk of contaminating ground or surface water

(xvi) Chemicals must be applied only at the recommended rates for the target pest/ weed.

(xvii) Chemicals should not be transported to the field in bulk to avoid dangers of accidents.

(xviii) Avoid spraying during windy conditions to avoid chemical drift from the application point. This is particularly important when spraying near special conservation areas.

Instruction 164: Records of chemical use shall be maintained, including training, types of chemical and their rates of application, safety issues that arise and how they are dealt with, among others

More detail on arrangements for field operations are given in the SPGS Community Tree Planting Guidelines of Uganda quoted above, Chapter 12, which deals with safe use of herbicides. The chapter includes, among others:

• Planning for spraying

• Rates of use of chemicals

• Equipment and tools used

• Safety and operational matters

• Training of spraying gangs

• Disposal of empty containers

• Calibration of knapsacks to determine how much chemical and how much total solution to use to achieve the desired control effect

¶ Wind Damage

Instruction 165: Wind damage involving more than 0.1 ha shall be reported on the Fire Report Form using such headings as are applicable. Additional information on soil texture and depth, rooting depth, density of crop, pruned height, health and vigour of the crop etc. shall be given.

¶ Control of Termites

The aforesaid notwithstanding, control of termites is described below in more detail because termites are the most widespread pests in planted trees in Uganda. Termites also attack a wide range of species. The details below have been extracted from Tree Planting Guidelines for Uganda, by Jacovelli, et al, 2004.

Instruction 166: Where termite infestation is an obvious threat, the following management practices are the first line of defence:

• Use healthy and vigorous planting stock

• Plant the seedlings as early as possible in the rainy season to encourage vigorous growth

• Ensure seedlings are well watered immediately before planting out to limit stress immediately after planting

• Use species or provenances that are resistant to termites

• The above measures may be supplemented by digging up the mounds and destroying the queen, where the termites are mound-forming.

Fungus-growing termites are the most destructive. They prefer to eat dead plant material. Their attacks are thought to be related to soils with low organic matter content. This is because such soils do not contain enough food for termites to live on, and thus, they resort to feeding on living plant material.

Instruction 167: Compost or well-rotted green manure may be added to the soil to increase the organic matter in the soil. However, in some cases, the organic matter might attract termites and when the organic matter is finished, the termites might attack the trees.

Indigenous plant species are more resistant than exotics. Table 8 gives a number of tree species and shrubs that have proved to be termite resistant, and the plant parts that can be used for preventing termite attack.

Table 8: Some Plants with Termite Control Properties